Dispatches from MacDowell

April 2025

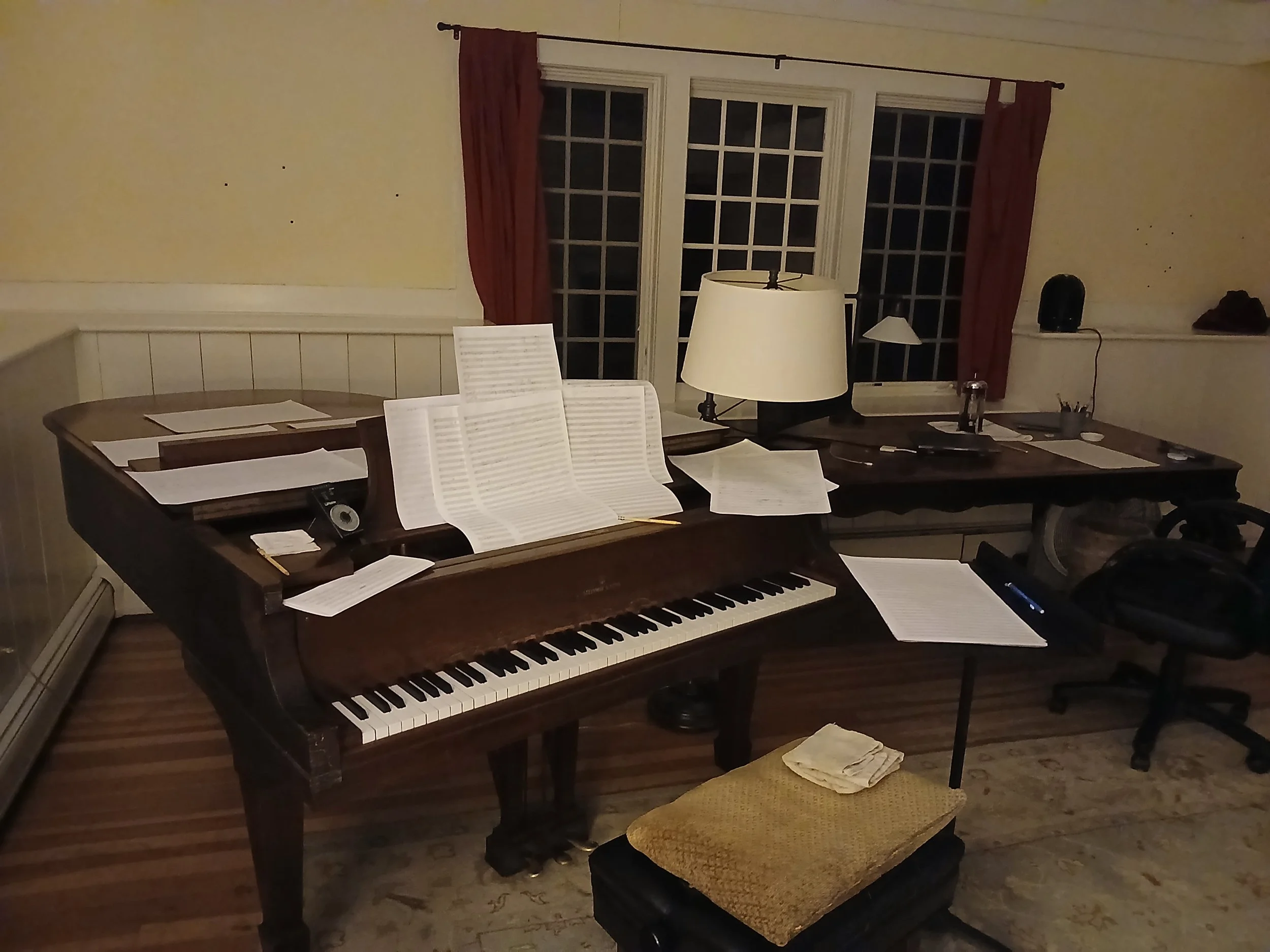

My first residency at MacDowell was in winter 2008. It was a particularly long and cold winter and I had only been living on the east coast for about 5 years. I was just about to find out about being awarded my first post in music composition at Clark University, but during the residency, I had no idea where I was going to wind up. It was a peak experience in part because of this timing – not knowing where I was going to land, but having accumulated all I was going to harvest from my years as a student. Then, MacDowell culminated a season on the road, away from the semblance of an apartment in Cambridge that I was calling home. I am not sure I fully understood how stuffy the five years of graduate school made me feel, but I was certainly aware of how freeing the experience of being at MacDowell was for me. With no money and no commitments to the future it was a time of living completely in the present moment.

It was also MacDowell's 100th anniversary year, and so a who's who of luminaries were coming and going: Fred Hersch and Meredith Monk were among my colleagues there in music. I learned quite a lot from them, and was also curious about who I could learn from in the other arts. I met the film maker L.M. Kit Carson, fresh off of year shooting for a documentary about three countries in Africa, and we became fast friends. I later worked with Kit on the music and sound design for Africa Diaries, a project that became a formative experience for me. Kit and I would play pool in the main hall most evenings. One evening, we played while he put Stuck in the Middle with You on repeat. We must have listened to it fifty times. He wanted to know what Quentin Tarantino saw in the song. Kit knew everyone in the film industry and was one step away from everyone else. He and I bonded on our Catholic upbringings and being raised out west, him in Texas, myself in Arizona. He always kept a bottle of Knob Creek in the kitchen and so when I returned to MacDowell in 2025 for a third residency, I stocked the fellow's kitchen cabinet with Knob Creek in his honor.

This last residency at MacDowell was brilliant in new and different ways. It was my first visit since the pandemic. Artists seemed more eager than ever to share their work. At my second residency in 2015, I don't remember attending many presentations. This time, there was one every single night. One presentation that resonated deeply with me was by Jessica Fertonani Cooke. Her presentation on the vibrations of saguaro cactus reveals that ancient life surrounding us pulses in the same ways as the human body. Her presentation touched on the promise of universality – that there are scientific principles, easily and powerfully expressed artistically, that illuminate this truth of university. That we have a shared experience – and shared destiny – on earth. In an era of mass disinformation campaigns and a fractured civic sense of reality, these explorations by Cooke seem more important than ever for how they might instruct new ways of communicating.

In listening to Cooke's presentation, I could not help but think of the traditional wisdom around finding one's voice. Perhaps this old prerogative is more important than ever as a resistance to hegemony – indeed it may be necessary for survival. But it seems unavoidable that a genuine pursuit of the personal voice inevitably leads one to ask how their work will be received and this has the nasty effect of bringing artists closer to the sphere of late capitalism. Often, without our even realizing it, art is co-opted by institutions looking to commercialize individual artistry (which has the ironic consequence of creating an audience cynical to diverse expressions).

These tensions play out in the world of music through the question of the familiar and unfamiliar. Yet, how something sounds (a primary metric in its marketability), has come to interest me less anyway. In recent years, what has begun to interest me more is the idea of musical time.

A quote from Caroline Winterer:

“Unlike space, time is maddeningly elusive. We somehow know it is there, but we need material objects to make it real to our senses. We experience time in terms of space: the hands of a clock ticking forward, the sun rising and setting, children growing into adults. This is why many scholars agree that it is more interesting and rewarding to see time not as a brute fact of nature but as an artifact created by human beings to communicate about this world of mundane projects and the cosmic world of the divine. If we see time as a social experience, we can suspend judgement about whether time objectively exists ’out there’ and instead study the many different forms that the experience of time has taken in the numerous societies that left their chronometrical fingerprints behind. What seems obvious and natural in one society seems strange and wrong in another.”

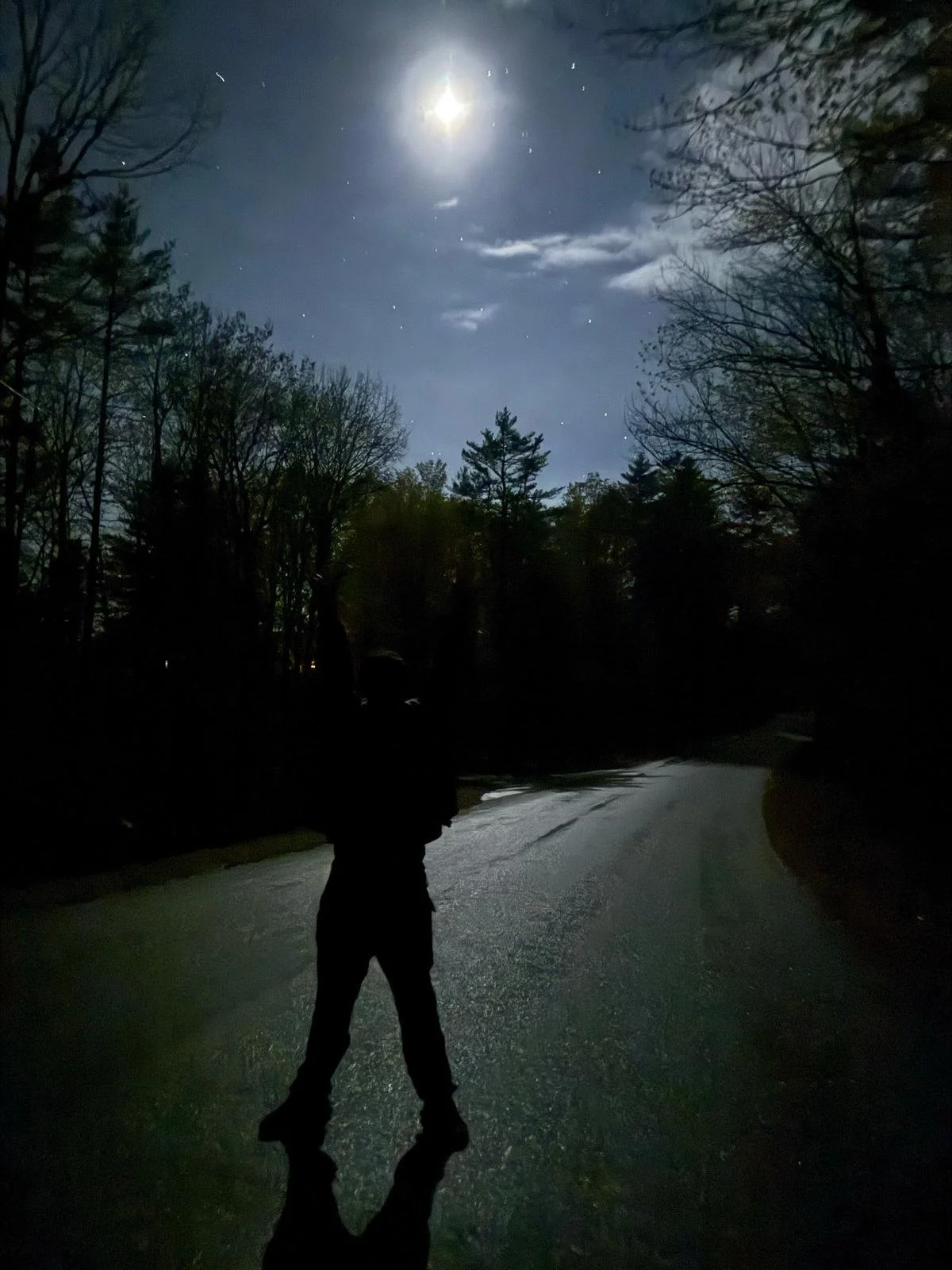

Musical time is perhaps most akin to dream time. A concert is a time where we can let our souls wander in both a communal and deeply personal experience. What can take us out of musical time is the intellectual question about whether we understand or ‘get’ the music. The ever-evaluative intellect is always sizing up worth and value, but more than that, I believe it is actually afraid of the freedom of musical time. A time that takes us away from the intellectual questions of our life: the past, the future, who we think we are, what others think of us, what’s going to happen to us, our body, our loved ones. Musical time is elusive and has the ability to suspend what we think, experience, or intellectualize, as clock time. What a beautiful saying it is to let the mind wander. Or as Winterer might say, to suspend our collective judgement about whether our social experience of time exists.

In this metaphysical bridge between personal and communal states and experiences, music has the capacity to elicit deep empathy and connection for all of us. Music has the potential to transport us away from our sense of our physical corporeal selves, loosening our masks, and, ultimately, our sense of otherness. There is a mysterious link to this loosening of ourselves and the suspension of what we think of as time. Our selves, a construct so inexplicably linked to our sense of memory, sits upon a stream of time. Formative events recalled, then recalled again, and again, or perhaps forgotten?

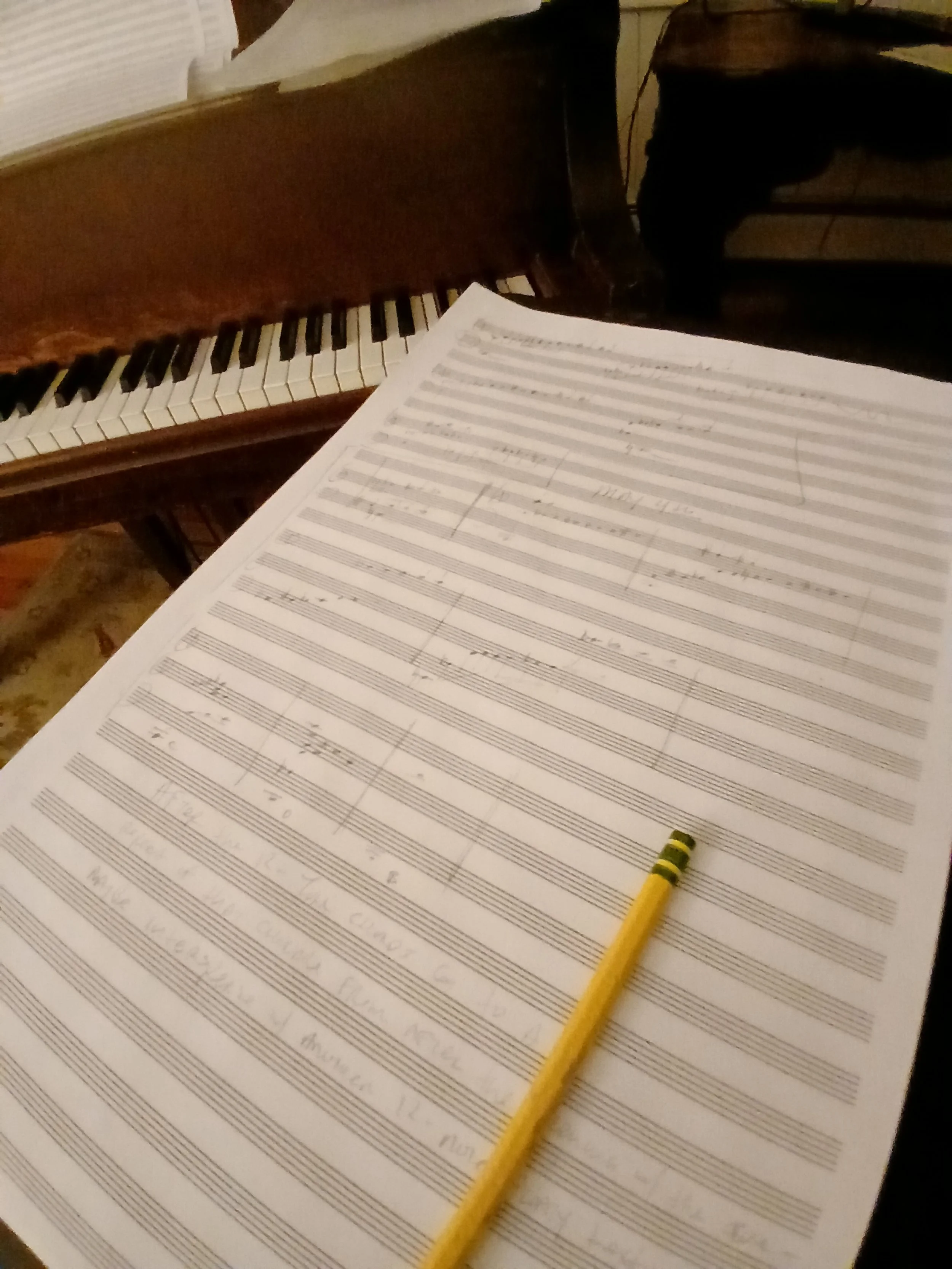

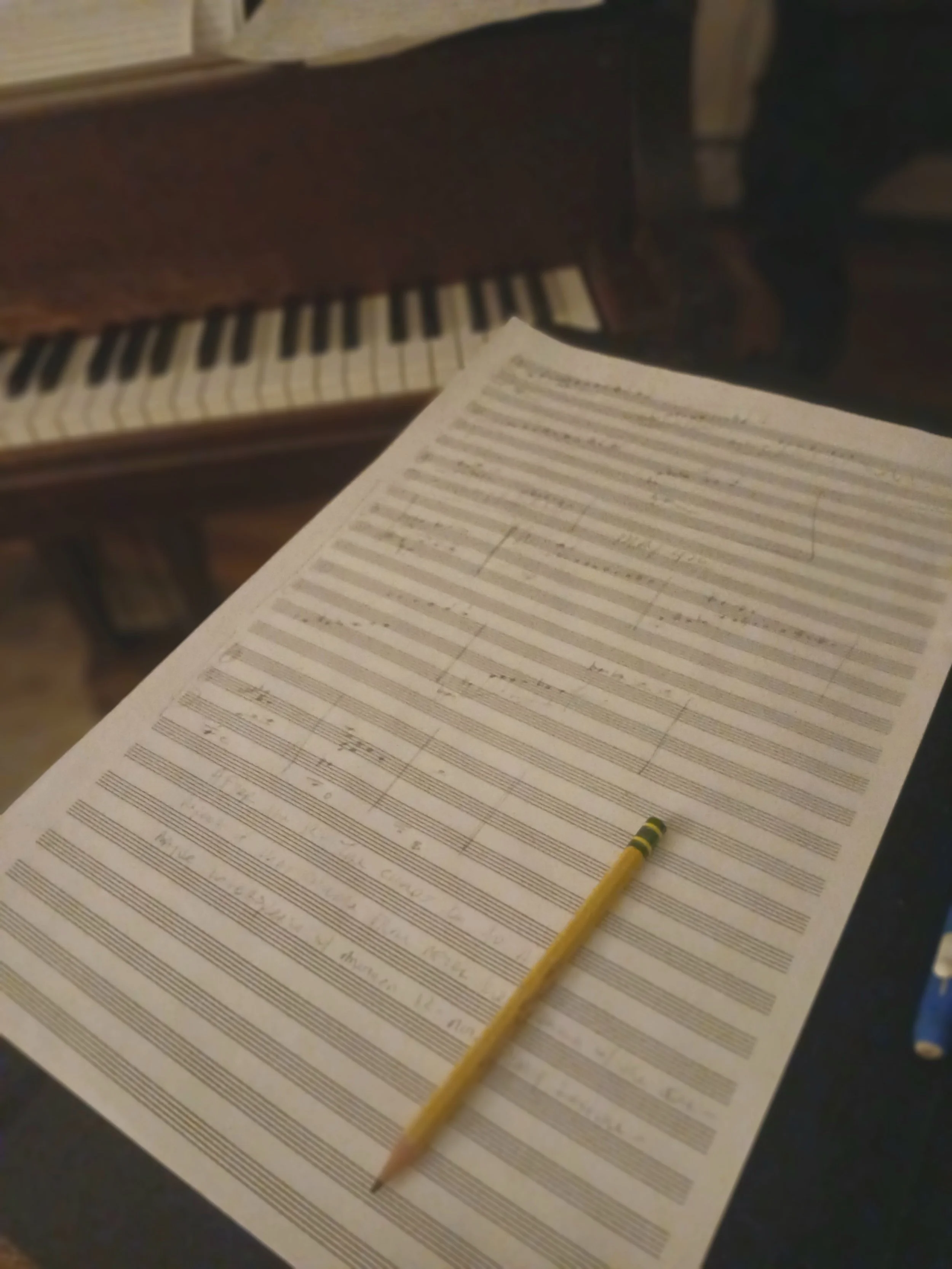

In the two works I presented at MacDowell, I question how our sense of self is created, shared and questioned, through memory and time.

Oblivion is a chamber opera completed in 2022 and filmed in 2023. The opera, borrowing from Dante’s Purgatorio, is about two amnesiac wanderers in purgatory confronting two religio-philosophical archetypes. To contrast with the influence of Dante, we set the opera in an American motel diner. The short story is that an amnesiac walks into a bar and asks two religio-philosoph-archetypes who he is.

In Moondial, I take another approach to identity by having the performer confront themselves – their digital avatar. The music is cast as a ritual to be performed, both in video or in a live performance, over and over again, suggesting that the work itself is a realization or manifestation of some cosmic cycle, or, to put it another way, a cosmic cycle that we know nothing of, is made tangible or touchable through a mapping of music on to it, perhaps in the way we map what we call time onto the particular cosmic thread of the universe for which we have yet to find a name.

In the end, what MacDowell continues to offer me- through friendships like Kit’s, through the insights of fellow artists, through the quiet hours of work and the shared vibrations of this place- is a reminder that our creative lives unfold along currents far larger than ourselves. Musical time, dream time, communal time: each invites us to loosen our grip on the fixed narratives of who we are and how we are meant to be understood. In that suspension, empathy becomes possible. Connection becomes possible. And perhaps, for a moment, we glimpse a world where the boundaries between self and other soften, where memory becomes a living, shifting companion, and where art returns us to the simple, profound truth that we are all moving together through a universe whose rhythms we only partially comprehend. Here at MacDowell, those rhythms feel just a little more audible.